As the Civil Rights movement started taking hold in the mid-1950s, many African American entertainers were vocal in their support. Louis Armstrong stayed silent. Until, that is, September 17, 1957.

As the Civil Rights movement started taking hold in the mid-1950s, many African American entertainers were vocal in their support. Louis Armstrong stayed silent. Until, that is, September 17, 1957.

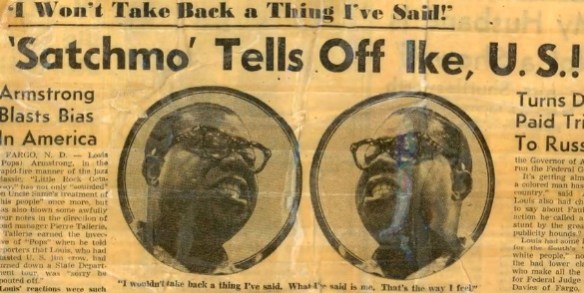

That night, in Grand Forks, North Dakota, Armstrong blasted President Dwight Eisenhower for his lack of action to make Governor Orval Faubus obey the law. This was in an interview conducted by a 21 year old University of North Dakota journalism student named Larry Lubenow.

Journalist David Margolick wrote about the incident in The New York Times in September 2007 in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the integration of Little Rock Central High School. He recounted how the story, written for the Grand Forks Herald, was picked up all over the country. The entire Margolick piece can be read here. Margolick tells that when Armstrong was given the chance to back off the comments, he asserted that he meant all of it.

On September 24, 1957, the night that the 101st Airborne was being mobilized to come into Little Rock, Armstrong sent Eisenhower a telegram again criticizing him for lack of action. He used colorful language which sarcastically spoofed the “Uncle Tom” moniker which some of his critics had bestowed when they felt he was not doing enough for Civil Rights. The Eisenhower Presidential Library has a copy of that telegram. The incident between Satchmo and Ike was the basis for two different plays: Terry Teachout’s Satchmo at the Waldorf and Ishmael Reed’s The C Above C Above High C.