The new Arkansas Civil Rights History Audio Tour was launched in November 2015. Produced by the City of Little Rock and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock allows the many places and stories of the City’s Civil Rights history to come to life an interactive tour. This month, during Black History Month, the Culture Vulture looks at some of the stops on this tour which focus on African American history.

The new Arkansas Civil Rights History Audio Tour was launched in November 2015. Produced by the City of Little Rock and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock allows the many places and stories of the City’s Civil Rights history to come to life an interactive tour. This month, during Black History Month, the Culture Vulture looks at some of the stops on this tour which focus on African American history.

Completed in 1918, Taborian Hall stands as one of the last reminders of the once-prosperous West Ninth Street African-American business and cultural district. West Ninth Street buildings included offices for black professionals, businesses, hotels, and entertainment venues. In 1916, the Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a fraternal insurance organization, hired local black contractor Simeon Johnson to enlarge an existing building to accommodate their activities, other offices and a ballroom.

During World War I, black soldiers from Camp Pike came to the Negro Soldiers Service Center here. In World War II, Taborian Hall was home to the Ninth Street USO, catering to black soldiers from Camp Robinson. By 1936, Dreamland Ballroom hosted basketball games, boxing matches, concerts and dances.

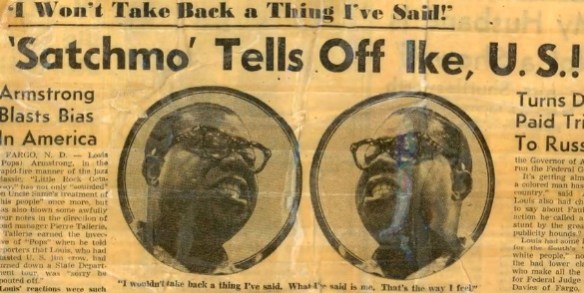

A regular stop for popular black entertainers on the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” Dreamland hosted Cab Callaway, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, B.B. King, Earl “Fatha” Hines and Ray Charles. Arkansas’s own Louis Jordan also performed here. Between the 1960s and 1980s, West Ninth Street declined, and many buildings were demolished. In 1991, Taborian Hall was renovated to house Arkansas Flag and Banner. Once again, Dreamland Ballroom hosts concerts and social events.

The app, funded by a generous grant from the Arkansas Humanities Council, was a collaboration among UALR’s Institute on Race and Ethnicity, the City of Little Rock, the Mayor’s Tourism Commission, and KUAR, UALR’s public radio station, with assistance from the Little Rock Convention and Visitors Bureau.

The Hot Sardines will be in concert tonight at Wildwood Park for the Arts. The music will start at 8pm; tickets range from $35 to $75.

The Hot Sardines will be in concert tonight at Wildwood Park for the Arts. The music will start at 8pm; tickets range from $35 to $75.