Courtesy of Paul Edwards to the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture

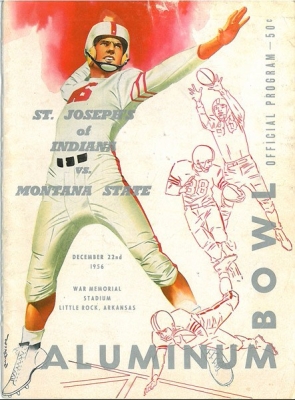

Bowl season is upon us! In 1956, Little Rock was home to the inaugural (and only) Aluminum Bowl.

On December 22, 1956, the city hosted the NAIA national championship game between Montana State University and St. Joseph’s College (of Indiana). This was the first time the NAIA had a football championship.

Originally the game was set to be played in Shreveport, Louisiana. But because some NAIA schools were integrated, teams with integrated rosters were forbidden by a state law passed by the Louisiana legislature.

The Little Rock Chamber of Commerce and others worked to bring the game to War Memorial Stadium. Because of the importance of the aluminum industry in Central Arkansas, the name Aluminum Bowl was chosen. Both ALCOA and Reynolds were major sponsors of the event.

The game, which was aired on CBS TV and radio, was played on a rain-soaked muddy field and turned into a defensive slugfest. Both teams only got close to scoring once. The score ended up a 0 to 0 tie, so the teams were declared co-champions. The rain kept the crowds away as only 5,000 people showed up leaving 33,000 empty seats in the stadium. Miss Arkansas Barbara Banks, who had been wearing a dress made entirely out of aluminum, spent the game covered up to keep the dress dry.

The next year, the game went to Saint Petersburg, Florida, where it was rechristened the Holiday Bowl. The Little Rock outing would mark the only appearance by either team in the NAIA championship game. Both teams subsequently switched to NCAA competition. As of the spring of 2017, St. Joseph’s has suspended operations because of financial shortcomings.

It has been said that Little Rock leaders had wanted to get the Aluminum Bowl game to showcase that Little Rock was a progressive Southern city when it came to race relations. By 1956 the buses and the public library were integrated. However, both teams were faced with their African American players having to stay at separate hotels while in Central Arkansas (one in Little Rock, the other team in Hot Springs).

For more on the Aluminum Bowl, visit the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture.

Josephine Pankey was a real estate developer at a time that few women or few African American men were engaged in that profession. The fact that she was an African American woman who was developing real estate made her efforts even more remarkable.

Josephine Pankey was a real estate developer at a time that few women or few African American men were engaged in that profession. The fact that she was an African American woman who was developing real estate made her efforts even more remarkable.