On February 23, 1960, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down a decision in the case of Daisy BATES et al., Petitioners, v. CITY OF LITTLE ROCK et al. This case had been argued before the Court in November 1959.

On February 23, 1960, the U. S. Supreme Court handed down a decision in the case of Daisy BATES et al., Petitioners, v. CITY OF LITTLE ROCK et al. This case had been argued before the Court in November 1959.

Daisy Bates of Little Rock and Birdie Williams of North Little Rock were the petitioners. Each had been convicted of violating an identical ordinance of an Arkansas municipality by refusing a demand to furnish city officials with a list of the names of the members of a local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. The question for decision was whether these convictions can stand under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Little Rock ordinance (10,638) was passed on October 14, 1957. It charged that certain non-profits were actually functioning as businesses and using non-profit status to skirt the law. Therefore it required the non-profits to disclose their members and sources of dues. North Little Rock passed an identical ordinance.

(Mayor Woodrow Mann was not present at the meeting of the LR Council when the ordinance was passed. But he signed all of the resolutions and ordinances approved that night. Ordinance 10,638 was the only legislation that night which had also been signed by Acting Mayor Franklin Loy. Mayor Mann crossed through Loy’s name and signed his own.)

Mrs. Bates and Mrs. Williams as keepers of the records for their respective chapters of the NAACP refused to comply with the law. While they provided most of the information requested, they contended they did not have to provide the membership rosters and dues paid.

After refusing upon further demand to submit the names of the members of her organization, each was tried, convicted, and fined for a violation of the ordinance of her respective municipality. At the Bates trial evidence was offered to show that many former members of the local organization had declined to renew their membership because of the existence of the ordinance in question. Similar evidence was received in the Williams trial, as well as evidence that those who had been publicly identified in the community as members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had been subjected to harassment and threats of bodily harm.

Each woman was convicted in the court of Pulaski Circuit Court, First Division, William J. Kirby, Judge. They were fined $25 a person. On appeal the cases were consolidated in the Supreme Court of Arkansas in 1958. The convictions were upheld by five justices with George Rose Smith and J. Seaborn Holt dissenting.

Mrs. Bates and Mrs. Williams then appealed to the U. S. Supreme Court. The pair’s legal team included Robert L. Carter and George Howard, Jr. (who would later become a federal judge). Little Rock City Attorney Joseph Kemp argued the case for the City. The arguments before the U. S. Supreme Court were heard on November 18, 1959.

The SCOTUS decision was written by Associate Justice Potter Stewart. He was joined by Chief Justice Earl Warren and Associate Justices Felix Frankfurter, Tom C. Clark, John M. Harlan II, William J. Brennan and Charles E. Whittaker. Justices Hugo Black and William O. Douglas wrote a concurring opinion.

The U. S. Supreme Court reversed the lower courts.

In sum, there is a complete failure in this record to show (1) that the organizations were engaged in any occupation for which a license would be required, even if the occupation were conducted for a profit; (2) that the cities have ever asserted a claim against the organizations for payment of an occupation license tax; (3) that the organizations have ever asserted exemption from a tax imposed by the municipalities, either because of their alleged nonprofit character or for any other reason.

We conclude that the municipalities have failed to demonstrate a controlling justification for the deterrence of free association which compulsory disclosure of the membership lists would cause. The petitioners cannot be punished for refusing to produce information which the municipalities could not constitutionally require. The judgments cannot stand.

In their concurring opinion, Justices Black and Douglas wrote that they felt the facts not only violated freedom of speech and assembly from the First Amendment, but also aspects of the Fourteenth Amendment. They wrote that the freedom of assembly (including freedom of association) was a principle to be applied “to all people under our Constitution irrespective of their race, color, politics, or religion. That is, for us, the essence of the present opinion of the Court.”

Neither the Gazette or Democrat carried any reaction from City leaders. There was a City Board meeting the evening of the decision. If it was mentioned, the minutes from the meeting do not reflect it.

Arkansas Attorney General Bruce Bennett, on the other hand, was very vocal in his outrage. The city laws were known as Bennett Laws because they had been drafted by him as ways to intimidate African Americans and others he viewed as agitators.

In 1960 Bennett was challenging Governor Orval Faubus for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination. In reaction to the to the Supreme Court he vowed that, if elected Governor, he would “de-integrate” (a term he proudly took credit for coining) the state.

For his part, and not to be outdone by the AG, Faubus fretted that the Court’s decision meant that Communists would be able to give money to the NAACP.

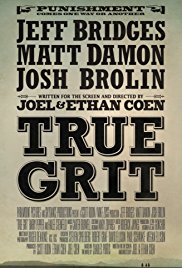

In 2010, the Coen Brothers released a new version of Charles Portis’ True Grit. (As a reminder, Portis had roots in Central Arkansas and was once a writer for the Arkansas Gazette.)

In 2010, the Coen Brothers released a new version of Charles Portis’ True Grit. (As a reminder, Portis had roots in Central Arkansas and was once a writer for the Arkansas Gazette.) Fifty years ago, former Arkansas Gazette reporter Charles Portis wrote a novel entitled True Grit. It is more than a work of literature, it is a work of art. In April 2018, the Oxford American will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of the novel with a series of events.

Fifty years ago, former Arkansas Gazette reporter Charles Portis wrote a novel entitled True Grit. It is more than a work of literature, it is a work of art. In April 2018, the Oxford American will be celebrating the 50th anniversary of the publication of the novel with a series of events. It is possible that journalist extraordinaire Roy Reed appears in archival footage of the Oscar winning documentary “Nine from Little Rock” (Documentary, Short-1964) and Oscar nominated Eyes on the Prize: Bridge to Freedom 1965 (Documentary, Feature-1988). First for the Arkansas Gazette and then for The New York Times, Reed was an eyewitness to history being made. What is not in doubt is that he is a character in the Oscar winning film Selma. In that movie, he was played by actor John Lavelle.

It is possible that journalist extraordinaire Roy Reed appears in archival footage of the Oscar winning documentary “Nine from Little Rock” (Documentary, Short-1964) and Oscar nominated Eyes on the Prize: Bridge to Freedom 1965 (Documentary, Feature-1988). First for the Arkansas Gazette and then for The New York Times, Reed was an eyewitness to history being made. What is not in doubt is that he is a character in the Oscar winning film Selma. In that movie, he was played by actor John Lavelle. Today marks the sixth time since Little Rock was permanently settled in 1820 that Ash Wednesday and Valentine’s Day fall on the same day. The previous years are 1866, 1877, 1923, 1934, and 1945.

Today marks the sixth time since Little Rock was permanently settled in 1820 that Ash Wednesday and Valentine’s Day fall on the same day. The previous years are 1866, 1877, 1923, 1934, and 1945. In the post-Civil War era, Mardi Gras was a major event in Little Rock. By the 1870s, newspapers would have stories for several days about preparations for parties and parades which would be followed by coverage summarizing the events.

In the post-Civil War era, Mardi Gras was a major event in Little Rock. By the 1870s, newspapers would have stories for several days about preparations for parties and parades which would be followed by coverage summarizing the events. On January 31, 1921, future “Little Girl from Little Rock” and Oscar nominee Carol Channing was born. Alas it was in Seattle.

On January 31, 1921, future “Little Girl from Little Rock” and Oscar nominee Carol Channing was born. Alas it was in Seattle.