On May 31, 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka II.

On May 31, 1955, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its ruling in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka II.

One year after the landmark Brown v. Board decision which declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional, the Supreme Court took up the case again. This time the focus was on the implementation of desegregation

The original Brown v. Board grew out of a class action suit filed in Topeka, Kansas, by thirteen African American parents on behalf of their children. The District Court had ruled in favor of the Board of Education, citing Plessy v. Ferguson. When it was appealed to the Supreme Court, Brown v. Board was combined with four other cases from other jurisdictions.

After handing down the 1954 decision, the Supreme Court planned to hear arguments during the following court session regarding the implementation. Because the Brown v. Board case was actually a compilation of several cases from different parts of the US, the Supreme Court was faced with crafting a ruling which would apply to a variety of situations.

In the arguments before the court in April 1955, the NAACP argued for immediate desegregation while the states argued for delays.

The unanimous decision, authored by Chief Justice Earl Warren, employed the now-famous (or infamous?) phrase that the states should desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

In making the ruling, the US Supreme Court shifted the decision-making to local school districts and lower-level federal courts. The rationale was that those entities closest to the unique situation of each locality would be best equipped to handle the distinct needs of those schools and communities.

The Supreme Court did make it clear that all school systems must immediately starting moving toward racial desegregation. But again failed to provide any guideposts as to what that meant.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court’s Brown II ruling, earlier in May the Little Rock School Board had adopted a draft of what became known as the “Blossom Plan” (named for the superintendent, Virgil Blossom). The thought process seems to have been that if the LRSD had a plan in place prior to a Supreme Court decision, it might buy it more time had the court ruled that things had to happen immediately.

The Blossom Plan called for phased integration to start at the senior high level. It anticipated the new Hall High School as having an attendance zone in addition to zones for Central and Mann high schools. But the way the zones were created, the only school which would be integrated at first would be Central High. The junior highs and elementary schools would be integrated later.

With no immediate remedy from the US Supreme Court, the NAACP – both nationally and locally – had little recourse other than expressing their unhappiness continuing to verbally protest the lack of immediate desegregation. (This is an oversimplification of the NAACP efforts, but points out that their options were very limited.)

Another historic high school graduation took place on May 28, 1958. It was the first graduation ceremony for Little Rock Hall High School.

Another historic high school graduation took place on May 28, 1958. It was the first graduation ceremony for Little Rock Hall High School. Principal Terrell E. Powell (who would be tapped as superintendent of the district in a few months) presided over the ceremonies. Superintendent Virgil Blossom (whose daughter had graduated from Central High the day before) spoke briefly to introduce the School Board members. One of them, R. A. Lile, presented the students with their diplomas.

Principal Terrell E. Powell (who would be tapped as superintendent of the district in a few months) presided over the ceremonies. Superintendent Virgil Blossom (whose daughter had graduated from Central High the day before) spoke briefly to introduce the School Board members. One of them, R. A. Lile, presented the students with their diplomas. On May 27, 1955, on the stage of Robinson Auditorium, the Dunbar High School senior class graduated. This academic year marked not only the 25th anniversary of Dunbar’s opening, but it was the last year that the school building would offer junior high through junior college classes.

On May 27, 1955, on the stage of Robinson Auditorium, the Dunbar High School senior class graduated. This academic year marked not only the 25th anniversary of Dunbar’s opening, but it was the last year that the school building would offer junior high through junior college classes. May 25, 1959, was not only the Recall Election Day, it was the last day of school for the Little Rock School District’s elementary and junior high students.

May 25, 1959, was not only the Recall Election Day, it was the last day of school for the Little Rock School District’s elementary and junior high students. The Little Rock School District’s annual celebration of the arts in the schools, Artistry in the Rock starts today and runs through Friday, March 15.

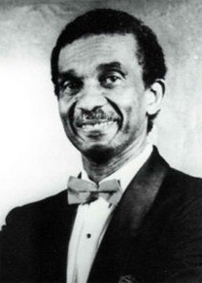

The Little Rock School District’s annual celebration of the arts in the schools, Artistry in the Rock starts today and runs through Friday, March 15. Arthur Lee (Art) Porter Sr. was a pianist, composer, conductor, and music teacher. His musical interest spanned from jazz to classical and spirituals.

Arthur Lee (Art) Porter Sr. was a pianist, composer, conductor, and music teacher. His musical interest spanned from jazz to classical and spirituals.