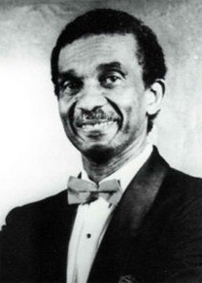

The triumphant trio who were retained by Little Rock voters.

May 25, 1959, was not only the Recall Election Day, it was the last day of school for the Little Rock School District’s elementary and junior high students. The results of that day’s vote would determine whether the ninth grade students would be in class come fall, or joining their older friends and neighbors in sitting out a school year.

While expectations that a new record of turnout would be set were off, over 25,000 of the 42,000 registered voters DID cast ballots in the May 25, 1959, Recall Election.

As the precinct results started coming in, some unexpected trends developed. Some of the boxes in the more affluent, western neighborhoods which had been expected to be strongly in favor of keeping Everett Tucker, Russell Matson and Ted Lamb were not providing the anticipated overwhelming numbers. Likewise, some of the more working class neighborhoods which had been projected to be strongly in favor of keeping Ed McKinley, Ben Rowland and Bob Laster were more receptive to keeping Tucker, Matson and Lamb.

As the night rolled onward, only Everett Tucker looked like a sure thing to be retained on the School Board. At one point in the evening it appeared that the other five members would be recalled. By the time they were down to four boxes still uncounted, the three CROSS-backed candidates were guaranteed to be recalled, but the status of Lamb and Matson was still undetermined. Finally, with only two boxes remaining, there was a sufficient cushion to guarantee Matson and Lamb would continue as board members.

Two boxes from the Woodruff school were uncounted at the end of Monday. They had 611 votes between the two of them, which was not enough to change any outcomes. They were being kept under lock and key to ensure there was no tampering with them.

Once it became apparent that Tucker, Lamb and Matson were retained, the STOP watch party erupted. Six young men hoisted the triumphant three on their shoulders and paraded them through the crowd. Dr. Drew Agar enthusiastically announced to the crowd, “Mission completely accomplished.”

At around 11:00 p.m. William S. Mitchell addressed the crowd. “This is a great awakening of our home town…I have never seen such a wonderful demonstration of community spirit.” He later went on to thank the thousands of people who volunteered in the effort.

At the CROSS headquarters, Ed McKinley and Rev. M. L. Moser were sequestered in a room poring over results. When it appeared that 5 of the 6 might be recalled, McKinley issued what turned out to be a premature statement.

Back at the STOP party, the celebration continued. While people knew that much work was still ahead, the men and women in attendance were enjoying a rare moment of joy after nearly two years of strife.

On July 19, 1945, future Little Rock City Manager Mahlon A. Martin was born in Little Rock.

On July 19, 1945, future Little Rock City Manager Mahlon A. Martin was born in Little Rock.