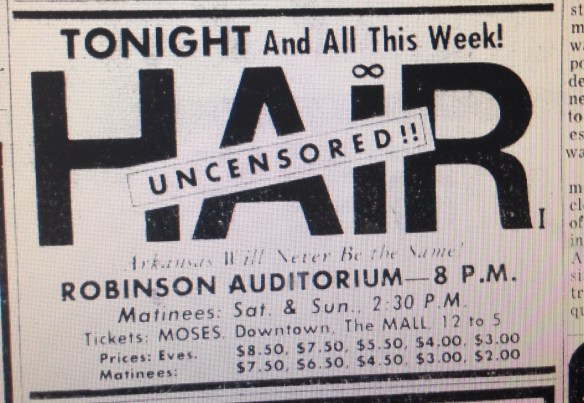

Ad for the original production of HAIR in Little Rock. Note the ticket prices. And that they could be purchased at Moses Music Shops.

The Tony winning musical The Music Man may have featured a song about “Trouble in River City” but the Tony nominated musical Hair brought trouble to this “river city” in 1971 and 1972.

In February 1971, a young Little Rock attorney named Phil Kaplan petitioned the Little Rock Board of Censors to see if it would allow a production of Hair to play in the city. He was asking on behalf of a client who was interested in bringing a national tour to Arkansas’ capital city. The show, which had opened on Broadway to great acclaim in April 1968 after an Off Broadway run in 1967, was known for containing a nude scene as well for a script which was fairly liberally sprinkled with four-letter words. The Censors stated they could not offer an opinion without having seen a production.

By July 1971, Kaplan and his client (who by then had been identified as local promoter Jim Porter and his company Southwest Productions) were seeking permission for a January 1972 booking of Hair from the City’s Auditorium Commission which was charged with overseeing operations at Robinson Auditorium. At its July meeting, the Commissioners voted against allowing Hair because of its “brief nude scene” and “bawdy language.”

Kaplan decried the decision. He stated that the body couldn’t “sit in censorship of legitimate theatrical productions.” He noted courts had held that Hair could be produced and that the Auditorium Commission, as an agent for the State, “clearly can’t exercise prior censorship.” He proffered that if the production was obscene it would be a matter for law enforcement not the Auditorium Commission.

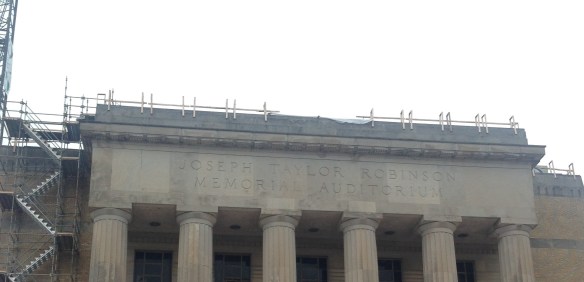

The Commission countered that they had an opinion from City Attorney Joseph Kemp stating they had the authority. One of the Commissioners, Mrs. Grady Miller (sister-in-law of the building’s namesake the late Senator Robinson who had served on the Commission since 1939), expressed her concern that allowing Hair would open the door to other productions such as Oh! Calcutta!

On July 26, 1971, Southwest Productions filed suit against the Auditorium Commission. Four days later there was a hearing before Judge G. Thomas Eisele. At that hearing, Auditorium Commission member Lee Rogers read aloud excerpts from the script he found objectionable. Under questioning from Kaplan, a recent touring production of Neil Simon’s Tony winning play Plaza Suite was discussed. That play has adultery as a central theme of one of its acts. Rogers admitted he found the play funny, and that since the adultery did not take place on stage, he did not object to it.

Judge Eisele offered a ruling on August 11 which compelled the Auditorium Commission to allow Hair to be performed. Prior to the ruling, some of the Auditorium Commissioners had publicly stated that if they had to allow Hair they would close it after the first performance on the grounds of obscenity. To combat this, Judge Eisele stated that the Commission had to allow Hair to perform the entire six day engagement it sought.

Upon hearing of the Judge’s ruling, Commissioner Miller offered a succinct, two word response. “Oh, Dear!”

In the end, the production of Hair at Robinson would not be the first performance in the state. The tour came through Fayetteville for two performances in October 1971. It played Barnhill Arena.

On January 18, 1972, Hair played the first of its 8 performances over 6 days at Robinson Auditorium. In his review the next day, the Arkansas Gazette’s Bill Lewis noted that Hair “threw out all it had to offer” and that Little Rock had survived.

The ads promoting the production carried the tagline “Arkansas will never be the same.” Tickets (from $2 all the way up to $8.50) could be purchased at Moses Melody Shops both downtown and in “The Mall” (meaning Park Plaza). That business is gone from downtown, but the scion of that family, Jimmy Moses, is actively involved in building downtown through countless projects. His sons are carrying on the family tradition too.

Little Rock was by no means unique in trying to stop productions of Hair. St. Louis, Birmingham, Los Angeles, Tallahassee, Boston, Atlanta, Charlotte NC, West Palm Beach, Oklahoma City, Mobile and Chattanooga all tried unsuccessfully to stop performances in their public auditoriums. Despite Judge Eisele’s ruling against the City of Little Rock, members of the Fort Smith City Council also tried to stop a production later in 1972 in that city. This was despite warnings from City staff that there was not legal standing.

Within a few years, the Board of Censors of the City of Little Rock would be dissolved (as similar bodies also were disappearing across the US). Likewise, the Auditorium Commission was discontinued before Hair even opened with its duties being taken over by the Advertising and Promotion Commission and the Convention & Visitors Bureau staff. This was not connected to the Hair decision; it was, instead, related to expanding convention facilities in Robinson and the new adjacent hotel. Regardless of the reasons for their demise, both bygone bodies were vestiges of earlier, simpler and differently focused days in Little Rock.

Over the years, Hair has returned to the Little Rock stage. It has been produced two more times at Robinson Center, UALR has produced it twice, and the Weekend Theater has also mounted a production. The most recent visit to Little Rock at Robinson Center, which was the final Broadway show before the building closed for renovations, was based on the 2009 Broadway revival. That production, was nominated for eight Tony Awards, and captured the Tony for Revival of a Musical. Several members of the production and creative team are frequent collaborators of Little Rock native Will Trice.

On June 7, 1920, the Little Rock City Council finally authorized the demolition of Little Rock’s 1906 temporary auditorium. The structure had originally been built as a skating rink which, when chairs were added, could be used for public meetings. Since the mid 1910’s, the City Council had discussed tearing it down over safety concerns. But since Little Rock had no other structure as a substitute, the Council kept delaying the decision.

On June 7, 1920, the Little Rock City Council finally authorized the demolition of Little Rock’s 1906 temporary auditorium. The structure had originally been built as a skating rink which, when chairs were added, could be used for public meetings. Since the mid 1910’s, the City Council had discussed tearing it down over safety concerns. But since Little Rock had no other structure as a substitute, the Council kept delaying the decision. In 1920, though there was not alternative space available, the Council decided that the structure had to come down. So City Engineer James H. Rice was authorized to have the building removed.

In 1920, though there was not alternative space available, the Council decided that the structure had to come down. So City Engineer James H. Rice was authorized to have the building removed. Today, Rice’s grandson, also known as Jim Rice is the COO of the Little Rock Convention & Visitors Bureau. In that capacity he is overseeing the renovation of Little Rock’s 1940 municipal auditorium – Robinson Center Music Hall.

Today, Rice’s grandson, also known as Jim Rice is the COO of the Little Rock Convention & Visitors Bureau. In that capacity he is overseeing the renovation of Little Rock’s 1940 municipal auditorium – Robinson Center Music Hall.