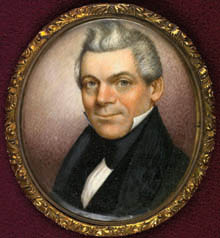

On December 29, 1829, future Little Rock Mayor Frederick G. Kramer was born in Halle, Prussia. In 1848, he immigrated to the United States. Kramer enlisted in the United States Army and served in the Seventh Infantry until his discharge at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, in July 1857. After his discharge, Kramer settled in Little Rock, and became a citizen in 1859. He married Adaline Margaret Reichardt, an emigrant from Germany, in 1857. They had six children Louisa, Mattie, Emma, Charles, Fred, and Henry.

On December 29, 1829, future Little Rock Mayor Frederick G. Kramer was born in Halle, Prussia. In 1848, he immigrated to the United States. Kramer enlisted in the United States Army and served in the Seventh Infantry until his discharge at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, in July 1857. After his discharge, Kramer settled in Little Rock, and became a citizen in 1859. He married Adaline Margaret Reichardt, an emigrant from Germany, in 1857. They had six children Louisa, Mattie, Emma, Charles, Fred, and Henry.

From 1869 to 1894, Kramer served on the Little Rock School Board. He was the first School Board president. Among his other civic activities were serving as president of the Masonic Mutual Relief Association, a founder of the Mount Holly Cemetery Commission, and a founder of Temple B’nai Israel. In 1875 he and F. A. Sarasin opened a mercantile business. Kramer later became the president of the Bank of Commerce.

Frederick Kramer was elected Mayor of Little Rock in November 1873. He served until April 1875, when a new Arkansas Constitution took effect.

From November 1869 through March 1875, the City Council President presided over City Council meetings and signed ordinances, performing many of the duties formerly ascribed to the Mayor. As such, during his Mayoral tenure from 1873 to 1875, Kramer was the Chief Executive of the City but did not preside over Council Meeting. When he had served on the City Council, however, Kramer had been elected President of the Council and had presided over Council meetings from October 1871 to May 1872

Kramer was returned to the Mayoralty in April 1881 and served three more terms leaving office in April 1887. His tenure as an Alderman and as Mayor overlapped with his service on the school board.

A new Little Rock elementary school which opened in 1895 on Sherman Street was named the Fred Kramer Elementary School in his honor. Though the building’s bell tower was removed in the 1950s, the structure still stands today. It now houses loft apartments.

Frederick G. Kramer died on September 8, 1896, in Colorado Springs, Colorado. A few months earlier, he had traveled there with his wife and daughter Emma to recuperate from an illness. He is buried in Oakland Cemetery.