As has been noted in a previous post, War Memorial Stadium was approved by the Arkansas General Assembly in March 1947. The work then began on the finalization of the location.

As has been noted in a previous post, War Memorial Stadium was approved by the Arkansas General Assembly in March 1947. The work then began on the finalization of the location.

Four cities were in the running: Little Rock, North Little Rock, Hot Springs, and West Memphis. Each of the cities was required to donate the land for the stadium, provide parking for it, and sell local subscriptions equivalent to $250,000 to raise money for it as well.

On May 19, 1947, the City Council approved Resolution 1,747 to donate the land for the stadium in Fair Park if Little Rock was selected. This was not the first mention of a stadium in City records. In March of 1947, the City Council had set aside land in Fair Park to use for a playground — with the stipulation that if it was eventually needed for a stadium, it would be relinquished for that purpose.

On August 9, 1947, the War Memorial Stadium Commission met in the House Chambers of the Arkansas State Capitol to select the location for the stadium. West Memphis dropped out prior to the meeting; they had not been able to raise the sufficient local funds. That left the three remaining cities. (Cities had until June 24 to file paperwork expressing their interest in applying and were to submit their proposals by August 1.)

Instead of meeting in a usual committee room, the meeting was held in the House Chambers of the State Capitol. The location for the meeting had been set because a large crowd was expected. And the attendance did not disappoint. City government and business leaders from all three cities turned out in full force.

The members of the Commission were Ed Keith, Chairman, Magnolia; Gordon Campbell, Secretary, Little Rock; Ed Gordon, Morrilton; Senator Lee Reaves, Hermitage; Senator Guy “Mutt” Jones, Conway; Dallas Dalton, Arkadelphia; Judge Maupin Cummings, Fayetteville; Dave Laney, Osceola; and Leslie Speck, Frenchman’s Bayou.

For several hours the nine heard proposals from the three cities. Little Rock’s location was in Fair Park, North Little Rock’s was near its high school, and Hot Springs was on land next to Highway 70 approximately 2.5 miles from downtown. Finally it was time to vote. After two rounds of voting, Little Rock was declared the winner on a weighted ballot.

The north shore’s leadership was magnanimous in their defeat. Hot Springs, however, was far from it. In the coming days they filed suit against the Stadium Commission alleging flaws in Little Rock’s proposal as well as improprieties by members of the commission. A preliminary decision sided with the state. Ultimately, Hot Springs’ relatively new mayor Earl T. Ricks opted to drop the suit. The Spa City’s business community was concerned that fighting the location might delay construction – and could negatively impact legislative and tourists’ feelings toward Hot Springs. (And it was entirely possible that the State Police could have been used to “discover” that there was gambling going on in Hot Springs.)

Though ground was broken later in the year, by December 1947, the stadium was still $250,000 shy of funding for the construction. This was after the state and Little Rock had previously both upped their commitments to $500,000 each.

The building did eventually open on schedule in conjunction with the 1948 Arkansas Razorback football games.

As for Mayor Ricks of Hot Springs, he moved to Little Rock to serve as Adjutant General of the Arkansas National Guard during the governorship of Sid McMath. He later held leadership positions in the National Guard Bureau in Washington DC. He died in 1954 at the age of 45. Among the ways he was memorialized was a National Guard armory in Little Rock, which stood in the shadow of War Memorial Stadium.

Tonight a new Miss America will be crowned. The competition has had a tumultuous year with many changes behind the scenes as well as alterations to the event format.

Tonight a new Miss America will be crowned. The competition has had a tumultuous year with many changes behind the scenes as well as alterations to the event format.

As has been noted in a previous

As has been noted in a previous  Though President Truman was in Little Rock for a military reunion, he did conduct some official business while here. In his Presidential role, he spoke at the dedication of War Memorial Park on June 11, 1949.

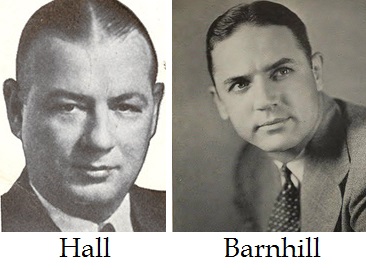

Though President Truman was in Little Rock for a military reunion, he did conduct some official business while here. In his Presidential role, he spoke at the dedication of War Memorial Park on June 11, 1949. On March 18, 1947, Governor Ben T. Laney signed the bill into law which authorized the construction of War Memorial Stadium.

On March 18, 1947, Governor Ben T. Laney signed the bill into law which authorized the construction of War Memorial Stadium. Cleveland County, Arkansas, native Johnny Cash was the subject of the Oscar winning film Walk the Line. Although he never lived in Little Rock, he was a frequent visitor throughout his career.

Cleveland County, Arkansas, native Johnny Cash was the subject of the Oscar winning film Walk the Line. Although he never lived in Little Rock, he was a frequent visitor throughout his career. With his death today at the age of 99, a look at two visits Billy Graham made to Little Rock.

With his death today at the age of 99, a look at two visits Billy Graham made to Little Rock.