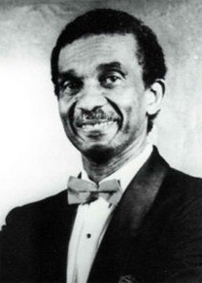

Arthur Lee (Art) Porter Sr. was a pianist, composer, conductor, and music teacher. His musical interest spanned from jazz to classical and spirituals. One of the new event spaces in the Robinson Conference Center is named in his memory.

Arthur Lee (Art) Porter Sr. was a pianist, composer, conductor, and music teacher. His musical interest spanned from jazz to classical and spirituals. One of the new event spaces in the Robinson Conference Center is named in his memory.

Born on February 8, 1934 in Little Rock, he began his music education at home. He played in church at age eight; played his first recital at twelve; and, by fourteen, hosted a half-hour classical music radio program on KLRA-AM. He earned a bachelor’s degree in music from Arkansas AM&N College (now UAPB) in May 1954. The next year, he married Thelma Pauline Minton. Following his marriage, he pursued graduate study at the University of Illinois, University of Texas and Henderson State University.

He began his teaching career at Mississippi Valley State University in 1954. When he was drafted into the Army, his musical talents were responsible for him being assigned as a chaplain’s assistant in New York. In the late 1950s he returned to Little Rock and taught at Horace Mann High School, Parkview High School and Philander Smith College.

He also started playing piano jazz in the evenings. This led to the creation of the Art Porter Trio, which became THE music group for events. Many musicians who came to Arkansas to perform in Little Rock or Hot Springs would often stop by and join in with Porter as he played. From 1971 to 1981 he hosted The Minor Key musical showcase on AETN. His Porterhouse Cuts program was shown in 13 states.

Often encouraged to tour, he instead chose to stay based in Arkansas. He did, from time time, perform at jazz or music festivals. He also performed classical piano with the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra, founded the Art Porter Singers, and created a music group featuring his four oldest children. Though Porter received many honors and awards, he found particular satisfaction in the “Art Porter Bill” enacted by the state legislature, which allowed minors to perform in clubs while under adult supervision. Porter’s children thus were able to perform with him throughout the state. Governor Bill Clinton, at the time a huge fan and friend of Porter, often joined Porter’s group on his saxophone.

In January 1993, Porter and his son Art Porter, Jr., performed at festivities in Washington DC for the Presidential Inauguration of his friend Bill Clinton. In July 1993, he died of lung cancer. Today his legacy lives on in the Art Porter Music Education Fund as well as in the lives of the many musicians and fans he touched. He was posthumously inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame in 1994.