On September 24, 1951, Pratt C. Remmel was nominated for Little Rock Mayor by the Pulaski County Republican Committee. This was the first time there had been a GOP mayoral nominee in Little Rock since the 1880s. It also set up a competitive General Election mayoral race for the first time in decades.

On September 24, 1951, Pratt C. Remmel was nominated for Little Rock Mayor by the Pulaski County Republican Committee. This was the first time there had been a GOP mayoral nominee in Little Rock since the 1880s. It also set up a competitive General Election mayoral race for the first time in decades.

Incumbent Sam Wassell, a Democrat, was seeking a third two-year term. First elected in 1947 (after being unsuccessful in his quest for the position in 1945), Wassell had survived a primary and runoff in the summer of 1951. So confident was Mayor Wassell that Little Rock would remain a Democratic city, he barely campaigned for the office in the General Election.

While Mayor Wassell was ignoring the “run unopposed or run scared” maxim, he was not incorrect that Little Rock remained a stronghold for the Democratic Party. Indeed there were no Republicans seeking office in Little Rock other than for mayor in 1951. Few, if any, Republicans had run for the City Council since Remmel had unsuccessfully made a race in the late 1930s.

In response to inquiries as to his lack of campaigning, Mayor Wassell averred that the voters had shown their support for him on July 31 and August 14. He continued that he did not see a reason to think the result would be different in November. The 68 year-old Wassell stated that if he could defeat a young opponent who had over a decade of experience as an alderman, he could certainly defeat a young opponent who had no governmental experience.

In the July 1951 Democratic mayoral primary, Wassell had been challenged by Alderman Franklin Loy and grocer J. H. Hickinbotham. Two years earlier, Wassell, seeking a second term, had dispatched Loy rather handily by a vote of 7,235 to 3,307. He fully expected that 1951 should produce the same results as 1949.

But Wassell was trying to buck recent history. Since 1925, no Little Rock mayor had won a nomination for a third term. One (J. V. Satterfield) had chosen not to seek a second term, while two (Pat L. Robinson and Dan T. Sprick) were defeated in their quest for two more years. Of those who served two two-year terms, a brace (Horace Knowlton as well as Charles Moyer in 1945) had not sought a third term. Moyer HAD sought a third two-year term during his first stint as mayor (1925-1929) but was defeated. Likewise R. E. Overman also lost his bid for a third term.

By trying to win a third term, Wassell was seeking to return to the era of the first quarter of the 20th Century where several of his predecessors had been elected at least three times. In his 1951 campaign, he was promising to stay the course of the previous four years. He answered his opponents’ ideas with a plan to continue providing services without having to raise taxes. So confident was he of besting Loy and Hickinbotham that he predicted a 3 to 1 margin of victory. A large horseshoe-shaped victory cake sat in a room at his campaign headquarters inside the Hotel Marion on election night.

The cake would remain uneaten.

When the results came in, Wassell had managed to get 5,720 votes to Loy’s 4,870. But with Hickinbotham surprising everyone (including probably himself) with 1,235 votes, no one had a majority. The race was headed for a runoff two weeks later to be held in conjunction with the other city and county Democratic elections on August 14.

The day after the July 31 election, the Arkansas Gazette showed an dazed Wassell with top campaign aids in a posed picture looking at the results. Further down the page, a jubilant Alderman Loy was surrounded by his wife and supporters. The differing mood reflected in the photos was echoed in the two men’s statements that evening. Wassell castigated his supporters for being overly-confident and not getting people to the polls. He further apologized to the Little Rock electorate for having to be “inconvenienced” with another election. Loy, on the other hand, was excited and gratified. He thanked the citizens for their support.

The day of the runoff, a 250 pound black bear got loose at the Little Rock Zoo after the zoo had closed and took 45 minutes to be captured and returned to its pit. Perhaps Wassell wondered if that bear was a metaphor for the Little Rock Democratic electorate. Much like the bear returned to its pit, Little Rock’s Democrats returned to Wassell — or at least enough did. Wassell captured 7,575 votes, while Loy received 6,544. The moods that night echoed those two weeks earlier. Wassell, his wife, and some supporters were combative towards the press (they were especially critical of the “negative” photo for which he had posed) while Loy was relaxed and magnanimous in defeat.

The closeness with which Mayor Wassell had escaped with the Democratic nomination was noticed. A group of businessmen started seeking someone to run as an independent. Likewise the Pulaski County GOP was open to fielding a candidate. At a county meeting held at Pratt Remmel’s office, the offer of the nomination was tendered to their host.

After he was nominated in September, Remmel (who was County Chair and State Treasurer for the GOP) visited with the business leaders who were trying to find someone to run. He had made his acceptance of the nomination contingent on being sure there would be a coalition of independents and possibly even Democrats backing him in addition to the Republicans.

Once he was in the race, Remmel was tireless. He blanketed newspapers with ads touting his plans and criticizing the lackadaisical attitude of his opponent. He made speeches and knocked on doors. He worked so hard that once during the campaign his doctor ordered him to 48 hour bedrest.

Mayor Wasssell, for his part, was confident voters would stick with party loyalty. But as the November 6 election day grew nearer some City and County leaders grew increasingly wary. Still, the Mayor rebuffed their concerns. Someone had even gone so far as to set up a campaign office for him in the Hotel Marion. But before it could officially open, it was shut down. (While the Mayor had criticized his supporters for being overly-confident in the July election, he apparently was not concerned about too much confidence this time around.)

Remmel had an aggressive campaign message promising better streets, more parking availability, a new traffic signalization plan, and the desire for expressways. His slogan was “a third bridge, not a third term” in reference to the proposed expressway bridge across the Arkansas River. (This would eventually be built and is now the much-debated I-30 bridge.)

The Saturday before the election, the Hogs beat Texas A&M in Fayetteville at Homecoming while a cold snap held the South in its grip. In addition to featuring both of those stories heavily, that weekend’s papers also carried the first ads advocating for Wassell. They were Wassell ads, in a manner. Ads from the County Democratic Committee, County Democratic Women, and Democratic officeholders in the county urged voters to stick to party loyalty. That would be the closest to a Wassell campaign ad in the autumn of 1951.

The night before the election, Wassell made his only radio appearance of the campaign while Remmel made yet another of his several appearances. Earlier that day in driving rain, there had been a Remmel rally and caravan through downtown, including passing by City Hall.

That evening, as the results came in, the fears of Democratic leaders were well-founded. Remmel carried 23 precincts. Wassell won two precincts and the absentee ballots. His victories in those three boxes were only by a total of 46 votes. Remmel won both Wassell’s home precinct (377 to 163) and his own (1,371 to 444).

In the end, the total was 7,794 for Remmel and 3,668 for Wassell.

And Little Rock was poised to have its first Republican mayor since W. G. Whipple had left office in April 1891, sixty years earlier.

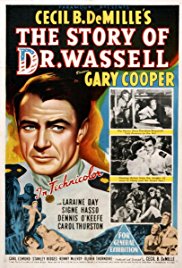

From April 24 to 26, 1944, future Oscar winner Cecil B. DeMille was in Little Rock for the world premiere screening of The Story of Dr. Wassell. This 1944 Paramount Pictures Technicolor release told the story of wartime hero Dr. Corydon Wassell. It would be nominated for the Oscar for Best Special Effects.

From April 24 to 26, 1944, future Oscar winner Cecil B. DeMille was in Little Rock for the world premiere screening of The Story of Dr. Wassell. This 1944 Paramount Pictures Technicolor release told the story of wartime hero Dr. Corydon Wassell. It would be nominated for the Oscar for Best Special Effects.

On January 9, 1866, the new Little Rock City Council held its second meeting after the post-Civil War resumption of municipal government. At that meeting, a special committee was created to meet with Gen. Williams who was the military commander for Arkansas. Mayor J. J. McAlmont, Alderman I. A. Henry, and Alderman Henry Ashley were authorized to discuss the creation of a permanent police force in Little Rock.

On January 9, 1866, the new Little Rock City Council held its second meeting after the post-Civil War resumption of municipal government. At that meeting, a special committee was created to meet with Gen. Williams who was the military commander for Arkansas. Mayor J. J. McAlmont, Alderman I. A. Henry, and Alderman Henry Ashley were authorized to discuss the creation of a permanent police force in Little Rock. One hundred and fifty three years ago today (on January 8, 1866), Little Rock City Hall resumed functioning after the Civil War. The City government had disbanded in September 1863 after the Battle of Little Rock. From September 1863 through the end of the war (on on through part of Reconstruction), Little Rock was under control of Union forces.

One hundred and fifty three years ago today (on January 8, 1866), Little Rock City Hall resumed functioning after the Civil War. The City government had disbanded in September 1863 after the Battle of Little Rock. From September 1863 through the end of the war (on on through part of Reconstruction), Little Rock was under control of Union forces. At the City Council meeting on December 19, 1929, Bernie Babcock presented the City of Little Rock with a Christmas present — the Museum of Natural History.

At the City Council meeting on December 19, 1929, Bernie Babcock presented the City of Little Rock with a Christmas present — the Museum of Natural History. On September 24, 1951, Pratt C. Remmel was nominated for Little Rock Mayor by the Pulaski County Republican Committee. This was the first time there had been a GOP mayoral nominee in Little Rock since the 1880s. It also set up a competitive General Election mayoral race for the first time in decades.

On September 24, 1951, Pratt C. Remmel was nominated for Little Rock Mayor by the Pulaski County Republican Committee. This was the first time there had been a GOP mayoral nominee in Little Rock since the 1880s. It also set up a competitive General Election mayoral race for the first time in decades. Following his second stint as mayor, Charles Moyer decided to not seek a fifth term leading Little Rock. It set the stage for the December 1944 Democratic primary. Alderman Sam Wassell and former Alderman Dan Sprick faced off in a particularly nasty race. As World War II was drawing to a close, there were charges leveled which questioned patriotism. With both men having service on the Little Rock City Council, there were also plenty of past votes on both sides which could become fodder for campaigns.

Following his second stint as mayor, Charles Moyer decided to not seek a fifth term leading Little Rock. It set the stage for the December 1944 Democratic primary. Alderman Sam Wassell and former Alderman Dan Sprick faced off in a particularly nasty race. As World War II was drawing to a close, there were charges leveled which questioned patriotism. With both men having service on the Little Rock City Council, there were also plenty of past votes on both sides which could become fodder for campaigns.